|

Cadências de significado que remetem às transformações do espaço urbano.

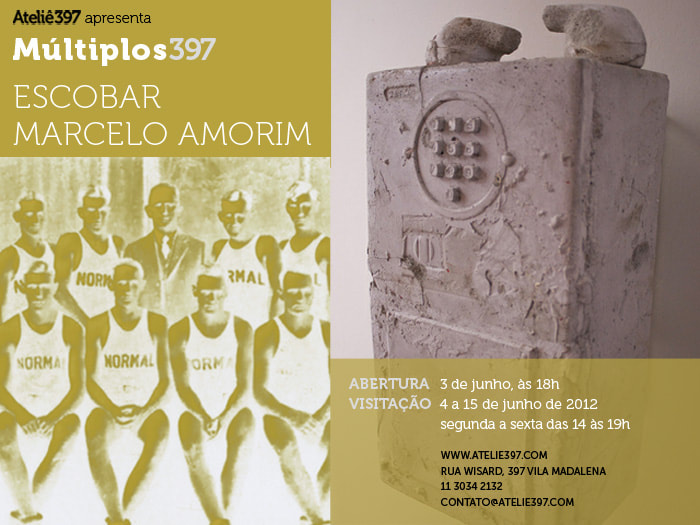

por Daniel Rubim Escobar é um artista urbano. Seja a pé, de skate, de carro ou de transporte público, seu olhar permanece atento ao universo visual da cidade. Não importa se são símbolos, objetos ou situações planejadas intencionalmente, ou apenas um acúmulo caótico que povoa o cotidiano da cidade, o artista absorve a visualidade característica das ruas de São Paulo de modo peculiar. Longe de fazer coro ao estereótipo urbano do grafite que, em alguns casos, mais serve a uma estetização que encobre a deterioração do espaço público, Escobar trabalha com símbolos carregados de sentidos, a fim de criar cadências de significado que remetem às transformações do espaço urbano. O trabalho Fóssil é construído sobre um destes símbolos. Escobar relembra os telefones públicos que funcionavam com fichas – os orelhões, como ficaram conhecidos popularmente – que, há alguns anos, eram muito presentes na cidade. Criando moldes de silicone a partir de um destes aparelhos, o artista reproduz suas formas em uma escultura em tamanho real, feita em concreto, material amplamente adotado na construção civil para erguer prédios, construir pontes, muros, calçadas e se transformou no solo natural da paisagem urbana. A escolha pelo concreto, um material que carrega em si o índice da urbanização e, ao mesmo tempo, assemelha-se às pedras e sedimentos que compõem um fóssil, amplia os sentidos da obra. Os orelhões, assim, aparecem como vestígios de “antigas civilizações”, encontrados em um “sítio arqueológico” de um bairro que, dos anos 80 para cá, sofreu sucessivas intervenções até se transformar no que é hoje. Onipresentes na cidade pelo seu baixo custo e grande durabilidade, os orelhões foram por certo tempo incorporados ao mobiliário urbano. Mas, hoje, a presença desse telefones é menor. Os aparelhos mais antigos foram substituídos pelos novos, que funcionam com cartões, e encontram-se majoritariamente dentro de shoppings, estações de metrô e outros espaços internos. Cidades são muitas vezes celebradas por seu dinamismo. Em busca do novo, o que é antigo é descartado, levando em conta apenas sua função primária, sem considerar seus aspectos simbólicos. O orelhão, presente em quase todos os quarteirões até a década de 90, era um objeto de uso público, coletivo, que guardavam em si o hábito de compartilhar o espaço comum da cidade. Gradualmente, ele foi substituído por telefones privados. Em um primeiro momento, pelos telefones fixos domiciliares, que garantiam a privacidade da ligação, mas ainda estavam atrelados a uma arquitetura. Em seguida, pelos telefones celulares, privados e portáteis, mas ainda limitados a apenas fazer ligações. Hoje, estamos na era dos smartfones, pequenos escritórios móveis. Há quem diga que o orelhão perdeu sua razão de existência. Não apenas por seu antiquado visual robusto, mas por seu uso, que permite que a vizinha ouça sua conversa e que faz com que 4 ou 5 famílias do mesmo quarteirão compartilhem um mesmo número de telefone. O orelhão, além da óbvia ferramenta de comunicação, é também ferramenta social, ponto de encontro, é onde viramos à esquerda para chegar no posto. |

Cadences of meaning that resemble the urban space transformation

por Daniel Rubim Escobar is an urban artist. If it is on foot, on the skateboard, inside a car or in public transport, his look always remains observant about the city's visual universe. It doesn't matter if there are symbols, objects, intentionally planned situations, or only a chaotic accumulation populating the city`s ordinary life, the artist absorbs the distinctive visuality from São Paulo in a singular way. Far from endorsing the urban stereotype of graffiti, that sometimes, is more up to standard an esthetics responsible for hiding the public space deterioration, Escobar works with meaningful symbols, in order to create cadences able to remind the urban spaces transformation. Fóssil, is a work created about one of those symbols. Escobar recalls the public phones that used to work once "paper cards" were put into their receivers - the "orelhões", as they became popularly known - used to be easily found in the city during past decades. Creating molds of silicone through one of those public phones, the artist transforms its proportions in a realistic sculpture, made in concrete, a material widely used in construction for raising buildings, bridges, walls, sidewalks and that ended up becoming the natural ground in the urban view. The option for concrete, a material that carries within itself the urbanization level, but at the same time resembles rocks and sediments that compound a fossil, expands the work's possible meanings. Therefore, the "orelhões" appear as traces from "ancient civilizations" found in "archaeological sites" of a neighborhood that since the 80's has been suffering successive interventions. Ubiquitous in the city because of their low cost and great durability, the "orelhões" were for a certain while incorporated to the urban "furniture". However, the presence of those phones is much lower nowadays, the older ones got replaced by new models that work with electronic cards, and are located mostly inside malls, subway stations and other internal spaces. Big cities are many times celebrated for their dynamism. Always looking forward, what is old ends up getting discarded, once it is considered only their primary function, forgetting about the symbolic aspects. The "orelhão", present in almost every corner until the 90`s, was a public and collective object, that carried in itself the habit for sharing the city's common space. Gradually, it was replaced by private phones. At first, by home telephones, that guaranteed the call`s privacy but was still linked to an architecture. More recently, there was the replacement for cell phones, limited only to calls. Now, we are in the smartphones era, small mobile offices. There are people who affirm that the "orelhão" doesn`t have any purpose nowadays. Not only because of the old fashioned aspect, but also for allowing your neighbor to listen to your conservation and obligating four or five families who live close to each other to share the same phone number. However, the "orelhão", besides the obvious utility as a communication tool, is also a social one, a meeting point, is where we turn left for arriving at the gas station. |